A Brief History of Enamel

INTRODUCTION TO THE ENAMEL TECHNIQUE

As far as we know, there was no specific name for enamel in the ancient world to distinguish it from other materials as for function, aesthetics or applicative method. This is due to the relative novelty for the Ancients, but also for the rather generic use of a single term to designate any shiny substance that can be either set or melted on metal and ceramics except for the gemstones. It seems, in fact, that the same word was used in antiquity for amber (considered a sort of “natural glass”), glass pastes and enamel. We have a witness of this in the Old Testament Hebrew word hashmal (Ezekiel 1:4), in the Greek word elektron (used in the Iliad by Homer to mean the coloured decorations on Achilles’ shield) and the Latin word electrum (used by the Latins to translate both hashmal and elektron). That is why it is even more difficult to trace a precise history of enamel in antiquity in absence of archaeological proofs (source: N. Dawson, Enamels, Londra, 1906; H. H. Cunynghame, European Enamels. 1906).

The word electrum was still in use until the late Middle Age, when the words smaltum and emallum (or variations thereof) appeared specifically to mean this material. We believe with a great level of certainty that these words come from the Gothic form smaltjan, which means “to melt”. From smaltum and emallum we get the word for enamel in the different European languages (Italian “smalto”, German “Email”, French “émail”, Spanish “esmalte”, Russian “эмаль”). Today, rare are the experts who claim an origin of smaltum and emallum from the Greek word smagdos, used in Byzantium to name the enamelled objects.

By the expression “porcelain/vitreous enamel”, we mean a crystal similar to glass, with addition of colouring pigments, grinded and melted at a high temperature on metal (500-900°C), that forms a stable and permanent bond with the metal base through a chain of chemical-physical reactions. Originally born for merely aesthetic purposes (i.e. to decorate and colourize the precious metals such as gold, silver, bronze or copper), in our time we appreciate enamel also for its protective functions that have made it possible for many enamelled works to survive the centuries to the present day.

Historically, enamelling has been applied for the first time on noble metals such as gold, silver and electrum (a gold-silver alloy at 20%) and only later also on bronze and copper. At present, iron, cast iron and aluminium are being enamelled by the industry on a large scale for decoration and as a protective coating.

I. The origins of enamelling

We believe that the cradle of this art might be the Mediterranean Sea, in the city of Mycenae and the island of Cyprus, some 3500 years ago. Obviously, the technique did not appear out of the blue, but was the result of a knowledge acquired over the millennia. We can identify many techniques and technologies that have been the precursors of enamel, such as:

1- Glass pastes and ceramic glazes as used in Egypt since the fifth millennium BC. These are the two materials more akin to enamel proper. In reality, the goldsmiths originally set glass-made gemstones directly in the metal.

2- Egyptian blue, also known in Italian as “smaltino”, invented about 2000 BC as a cobalt-based pigment with an addition of potash, applied as paint for decorative purposes.

3- Niello, consisting of the application of a black fusible powder on engraved metal. The technologies and the application method of niello are very similar to enamel. Invented in Egypt, the technique was already widespread in the Mediterranean Sea at the start of the Iron Age.

On the left: Glass paste, Egypt, 5th millennium BC. On the right: Tellus ring, 3rd millennium BC, gemstone inlay.

Then, c. 1500 BC, in the Mycenaean civilization, the goldsmith and the glassmaker invented a glass similar to gemstones that could melt on the gold, adhering and forming a permanent bond on the metal surface through a vitrification process at high temperature (source: A. H. Dietzel, Emaillierung, Springer-Verlag, 1981). The earliest enamels found in Mycenae and dated to 1425 BC were exclusively blue: since this moment, it is possible to study the history of enamelling through the archaeological findings with greater certainty. You should take notice, anyway, that the technique originally had, for a few centuries, a use restricted to jewels and religious objects, which makes it even more difficult to outline a full history of enamel art.

On the left: bronze daggers decorated with noble metal. On the right: a partially-enamelled cloisonné dagger, Mycene, 14th century BC, Athens Museum.

The most ancient findings of true enamel come from Cyprus during its golden age, at a time when the Mycenaean people found refuge on the island after the Achaean invasion. The high quality of the objects from this period show a deep knowledge of the technique, despite the rarity of the findings. The first known examples are the six golden rings dated to the 13th century BC, found in a tomb in Kouklia. Another noteworthy object is the 11th century BC Golden Royal Sceptre of Kourion, found in the ancient capital city of the island, whose round knot mounted on a 16 cm staff bearing decorations with white, lily and green enamels in little cells formed with a technique later known as “cloisonné” in French. Both the Sceptre and the Golden Rings are now in the Museum of Cyprus in Nicosia.

One of the six golden rings of Kouklia, Cyprus island, 13th century BC.

Knot of the Golden Royal Scepter of Kourion, Cyprus island, c. 1100 BC.

It is a subject of debate whether Ancient Egypt knew the art of enamelling in the late 18th dynasty period (1543-1292). On this issue, this is what famous Egyptologist T.G.H. James wrote about the necklace of the goddess Nekhbet on the pectoral of Tutankhamun (1332-1323 BC): “In many of the pieces of jewellery from Tutankhamun’s tomb a cloisonné technique with glass inlays has been observed. True cloisonné enamelling consists in filling the cloisons with powdered glass which is then fired in position, this results in inlays which completely fill, and are closely fixed in, their little gold enclosures. It has yet to be confirmed by close scientific examination that the technique was used in this case."

It is thus unsure whether we may say that these Egyptian findings were true enamel or not, at least before the Hellenistic age. Nevertheless, we should keep in mind that in the days of Tutankhamun Egypt had been entertaining economic exchanges with Cyprus since at least 50 years earlier in the form of importations from the so-called Peoples of the Sea, which may justify the presence of enamelling during the New Kingdom – once again originally from Cyprus.

II. The "enamel roads" of antiquity

From the 11th to the 7th century, we have no relevant archaeological findings and enamelling seems to be extinct. We must wait till the 7th century BC to see a sudden reappearance of the technique in different parts of the Old World, in the form of little enamelled details on filigree-decorated gold pieces.

The reason for this sudden rebirth of enamel is unknown, but we may make some conjectures: a key role might be that of the Assyrian Empire, that reached its maximum expansion right in the 7th century BC. As for Egypt, the supposed presence of enamel proper in Mesopotamia in the form of coloured glass on jewels of this period are insufficiently solid, but there are different elements in favour of a decorative use of enamelling by the Assyrians. In this respect, this is what writes archaeologist and historian Roger Moorey: “The whole question has been reopened by finds in the royal tombs at Nimrud in 1998-9, which included elaborate gold bracelets decorated with polychrome cloisonné work. Although some parts of it are clearly inlaid with semi-precious stones, some parts might be true enamel” (source: P.R.S. Moorey, Ancient Mesopotamian Materials and Industries: The Archaeological Evidence, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1994). It is noteworthy that the Assyrians mastered some techniques similar to enamelling, in particular the use of glass pastes and ceramic glazes that required identical technologies as enamelling on metal.

Amongst the indirect proofs, we can mention that, during the reign of Ashurbanipal (668-627 BC), Assyria controlled both territories where enamelling had already existed (such as Cyprus and, possibly, Egypt, as already mentioned) or that were going to use it in the next centuries. According to the historians, King Ashurbanipal was the greatest patron of art and literature of the time and this may have favoured the spreading of enamel within and without the borders of the Empire, combined with the Assyrian use to deport and mix the conquered populations

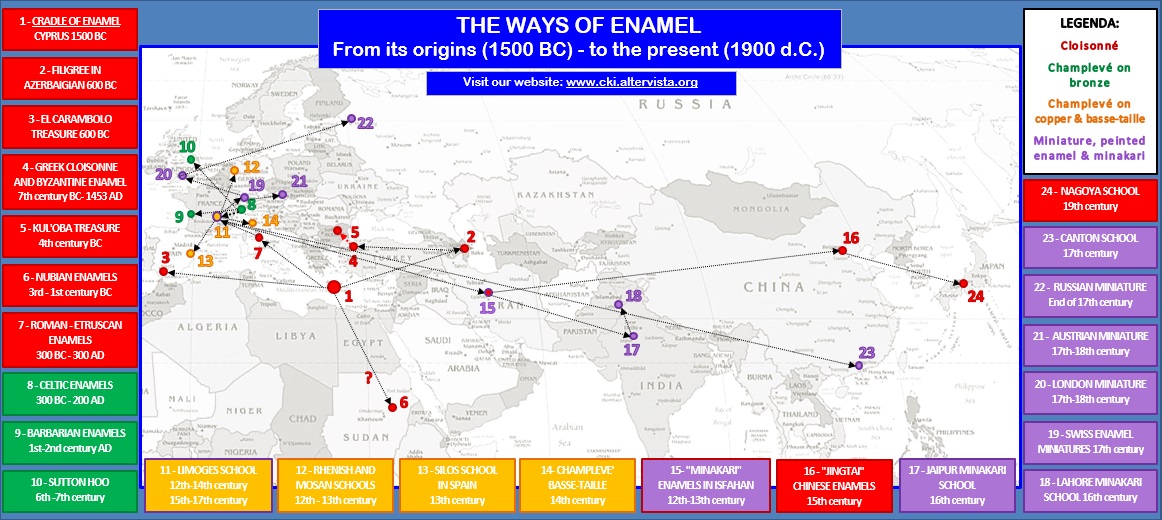

There were probably two distinct routes of enamel in antiquity:

- The Eastern Enamel Road was due to the Scythians, an ancient Iranian population of warriors that brought enamelling through two vectors. The oldest was the Asiatic vector through the Silk Road, witnessed in the findings of Ziwiye, Azerbaijan (sources: A.H. Dietzel, Emaillierung, Springer-Verlag, 1981; R.A. Higgins, Greek and Roman Jewellery, University of California Press, 1980) and that of Arzhan, Southern Siberia, at the borders with Mongolia (source: B. Armbruster). In these findings, both dated to the 7th century BC, we can find only white enamel in a few finishes. The second vector, through the Caucasus, was much later and its witness is the 4th century BC Kul’Oba treasure in Crimea.

Detail from a Scythian bracelet, Kul-Oba (Crimea, Ucraine), cloisonné enamel on gold, 4th century BC.

- The Western Enamel Road, on the contrary, was due to the Phoenicians. During the rule of Ashurbanipal, while subject to Assyrian power, the Phoenician city of Tyre in present-day Lebanon controlled a huge number of mining colonies including Carthage (Tunisia), Tharros (Sardinia) and, foremost, the cities of Tartessos and Cadiz in Andalusia (Spain). In these Spanish settlements we can notice the findings of golden jewels with little enamel finishes, such as the collar of the Treasure of El Carambolo (dated to the 8th-6th centuries) and the 7th-6th century BC collar of Gadir (source: Núria López-Ribalta), both of them not too different from the corresponding Assyrian and Scythian findings of the time.

Thanks to this market in the Mediterranean Sea, between the 7th and 4th centuries, enamel achieved Etruria in present-day Tuscany and Magna Graecia in present-day Southern Italy (source: Valérie Gonzalez, Gli smalti dell’Europa musulmana e del Maghreb). The execution in these cases is so accurate that we may suppose a well-known technique. In particular, in Etruria we found some enamelled golden jewels: one of them, dated to the 6th century BC, is today in the Metropolitan Museum, while another pair of swan-shaped earrings, dated to the 3rd century BC, are part of the Campana Collection in the Louvre Museum (Paris).

Etruscan earring, cloisonné enamel, 6th century BC

Dove-shaped Greek earrings from Milos, filigree enamel, 2nd century BC

A separate case is that of the Celts, who showed the practice to enamel bronze objects of different kinds with a vivid red colour since at least the La Tène period (5th century BC), while in the British islands enamel developed during the 3rd century BC. In this case, the technique was completely original, in the form of champlevé on engravings in the cast bronze. They will continue to practice this technique for many centuries. The mysterious origins of the Celts make it difficult to propose a definite theory on the origin of their enamel knowledge, but the hypothesis of a Caucasian homeland may link the Celtic enamelwork to the Scythian technique through the Eastern Enamel Road.

A territory of great fertility for the production of enamel jewels is Nubia, in present-day Sudan. Excluding a few fragments of enamelled metal dated to about 600 BC, of possible Egyptian or Mediterranean origin, it is in the Meroitic period (270 BC – 50 AD) that enamelling emerged as a national art. At this time that the local goldsmiths experimented with the champlevé technique and the earliest attempts at translucent enamel (Y.J. Markowitz, D. Doxey, Jewels of Ancient Nubia, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 2014).

A noteworthy example is the bracelet of Hathor from the excavations of Pyramid 8 in Gebel Barkal, dated to the period 250-100 BC, containing intense blue enamels obtained from cobalt oxide (in the form of Egyptian blue), while the purple is made of manganese and copper oxides and the green is a mixture of manganese, copper and iron oxides. Unluckily, the enamels look damaged by time but are still unique for the fact of being translucent, a true novelty for the Ancients. The greatest collection of golden enamelled jewels in Nubia is the late 1st century BC Treasure of Queen Amanishaketo (32-20 BC).

Bracelet from the treasure of Queen Amanishakheto, Nubia, cloisonné enamel, 35-20 BC.

LATE ANTIQUITY

Between the 1st and 2nd centuries AD, the Romans used the enamelling technique mainly for the decoration of daggers and scabbards used by the Roman army; it is in Rome, under the empire of Octavian Augustus, that a production of millefiori glass flourishes. With the expansion of their empire, the Romans spread enamelled objects of different origins and functions, such as fibulae and claps. There was the birth of a hybrid Gallic-Roman style of champlevé on cast bronze with a somewhat rough technique, we might say barbarized. The findings of medieval objects with compositions identical to those of Roman millefiori glass have revealed that the enamels from Ancient Rome have been recycled in medieval times for the creation of new works after the conversion of the Empire to Christendom, thus explaining the apparent lack of findings in the Imperial period. This is the same destiny as that of other construction materials of the time. We will deal with this phenomenon and its documentary and chemical proofs a propos of enamel in the Middle Age.

In the 4th century AD, the Huns from the east invaded Western Europe, forcing the Germans and Goths to flee, and re-introduced the Barbaric-Roman cloisonné enamel.

Staffordshire Moorlands Pan, Britain, champlevé on bronze, 2nd century AD

Early Middle Ages

After the Sack of Rome in 410 and the successful Barbarian campaigns, enamelling in Western Europe acquired an Eastern style with a lower technological quality. The artisans filled the cells with coloured glass similar to enamel, but not so perfectly adhering to the metal base and thus imperfectly called enamel.

Examples of Byzantine cloisonné enamel from the cover of a Gospel book.

From the 6th to the 8th centuries, there was a renewed interest in Celtic and British-Roman art in the British islands, undisturbed by the Barbarian invasions. The Anglo-Saxons learnt this technique and developed it through their goldsmithing art into a new style of insular cloisonné enamel decoration. Complex figures will not appear before the end of the 8th century.

A noteworthy example of this art is the Sutton Hoo burial ship (England, 7th century), where the excavations have made it possible to find wonderful gold filigree and cloisonné works decorated with red garnet and, more importantly, Roman millefiori glass re-used as enamel, mainly for the blue decorations.

Shoulder clasps from the burial ship of Sutton Hoo (7th century)

One of the most important objects left by the German peoples in Italy is the famous Iron Crown, created and perfected in more steps by the Ostrogoth, the Lombards and the Franks between 400 and 800 AD. The analysis by the University of Milan have demonstrated that the traditional history of this precious object is for the most part correct. According to both tradition and science, in fact, the gold of the Iron Crown comes from an earlier 4th century diadem (the presumed original owner was Constantine the Great, 272 – 337 AD), while the original plates enamelled with a potash-based glass are a later addition under the reign of Theodoric the Great (454 – 526 AD). The Crown probably underwent a series of minor restorations under the Lombards, until Charlemagne had 21 out 24 enamels replaced with new soda-based enamels on occasion of his coronation on 25 December 800. Since then, up to 32 kings and emperors wore the Iron Crown – the most important was probably Napoleon Bonaparte on December 2, 1804; the Crown is presently in the Cathedral of Monza. No doubt, this is the most important enamelled object of this period.

The Iron Crown, created over the 5th - 9th centuries, Cathedral of Monza.

Despite we know for sure that Byzantine enamel was born c. 600 AD, the most ancient enamelled icons that have survived the pass of time date to the 9th century. The reason is that, by the end of the 8th century, the so-called iconoclastic crisis began, when the Greek Church was on the verge of a schism between the defenders of the traditional iconography and those who opposed it, persuaded that it was necessary to destroy any form of sacred imagery.

Nevertheless, we have a few findings of cloisonné enamelling during this time from Georgia, presently exposed at the Museum of fine arts of Tbilisi, where we can also admire the Martvili and Khakhuli triptychs, dated to the 9th-12th centuries (source: Núria López-Ribalta). Georgia, in fact, is one of the few territories of Byzantine influence, which was not under the power of iconoclasm.

In continental Europe, from the 8th to the 9th century, the importation of cloisonné works from Constantinople inspires the Frank and German goldsmiths to produce true works of art, mainly in the form of reliquaries. In France, noteworthy is the holy water stoup of Saint Maurice of Agaune, with Persian-style motifs. Some of the most interesting enamelled objects of the Ottonian period (887-1000) are those commissioned by archbishop Egbert of Trier (950-993). In particular, we mention here the Altar-reliquary of the sandal of St. Andrew, the Pastoral Staff of Saint Peter the apostle and the reliquary of the Holy Nail, presently in the Treasure of the Cathedral of Trier.

Three reliquaries of Egbert: the Holy Nail - the Pastoral Staff of St. Peter - the sandal of St. Andrew

In Spain, where the Visigoths and Vandals found their Germanic kingdoms during the 8th century, enamel works arrive from Byzantium and a new local goldsmith school flourishes. With the earliest Islamic-Iberian kingdoms (711-718), this production is temporarily on hiatus. Enamel jewellery finds a new fertile terrain one century later under the Caliphate of Cordova. In 839, during a memorable ceremony witnessed by the contemporary chroniclers, the caliph of Cordova ʿAbd ar-Raḥman II received a delegation of the Emperor of Constantinople. During this event, the Eastern Emperor offered many gifts to the caliph, such as golden jewels with Byzantine enamels. The new exchanges with the Byzantine goldsmiths reintroduced the enamel jewellery art to al-Andalus. For religious reasons (the medieval Moslems believed that working and trading precious metal was a form of usury), the Islamic customers delegated the production of enamelled jewels to the Jewish goldsmiths, so that they acquired a sort of monopoly in this field. This goldsmithing tradition will influence the Christian production in the Reign of León, in particular the school at the Abbey of Saint Dominic of Silos (we will return on this point in the next chapter on the medieval schools). One of the rare examples of enamelling in Christian territory is the Victory Cross, commissioned by king Alphonsus III in 908 and a symbol of the modern Principality of Asturias. A separate case is the formation of a goldsmithing tradition in the Kingdom of Navarra, where enamel had already arrived from Central Europe with the typical traits of Carolingian art.

The Italian laboratories also become soon very famous for the production of perfect Carolingian-style enamellings, who export throughout Europe in the course of the 7th century. An important witness of late-Carolingian art is the Altarpiece of Saint Ambrose in Milan, created about 850 by great German-born goldsmith Volvinius.

Byzantine-style cloisonné from the Altarpiece of St. Ambrose in Milan (850, goldsmith Volvinius).

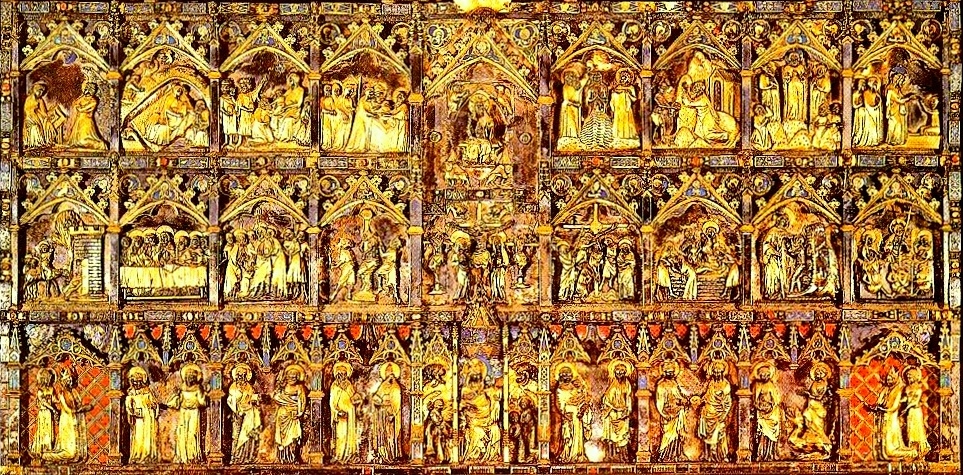

The Golden Altarpiece in St. Mark Cathedral (Venice) represents the most relevant product of Byzantine art, both for beauty and dimensions. Initially commissioned by doge Pietro Orseolo I (976-978) as an antependium and later enlarged, restored and adapted into an altarpiece by the will of his successors Ordelaffo Falier (1105), Pietro Ziani (1209) and Andrea Dandolo (1342). Today, the “Pala d’Oro” contains 250 plates with cloisonné enamel icons, created by Byzantine goldsmiths and/or raided in Constantinople during the Crusades.

Pala d'Oro in St Mark Cathedral, Venice, cloisonné enamel, 10th-15th century, 3.84-1.40 m.

The Holy Crown of Hungary needs a separate mention. Legendarily created at the pope’s orders for the crowning of King St. Stephen of Hungary on December 25, 1000 (exactly 200 years after Charlemagne), in reality the crown is the union of two separate diadems, both with enamelled icons, one with Greek and the other with Latin inscriptions, both datable to the 11th century. The Crown of St. Stephen is said to be the most noteworthy example of émail mixté, a hybrid between cloisonné and champlevé.

Crown of St. Stephen of Hungary, sunk or mixed enamel, 11th century

During the Carolingian period, we can witness the appearance of Gothic cathedral glass, where the glass was either coloured or enameled and assembled in tesserae, joined with each other with a lead frame. Stained blass was born. The most ancient example of stained glass was hand-painted in the 10th century by the monk Wernher for the Tegernsee Abbey in Bavaria.

In Spain, under the patronage of king Fernando I, King of Léon (1016-1065), and his consort Queen Sancha, many workshops are born, dedicated to cloisonné on gold and silver; most of them are presently part of the Treasure of St. Isidore of Léon in the Cathedral of Oviedo.

A curious example of iron-based objects: a religious image and a few discs, probably used as currencty. Cloisonné technique, 11th century. Found in the Haute Vienne. Museum of Fine Arts, Limoges.

From Conques to the Medieval Schools

During the last decades of the 11th century, in the city of CONQUES in France, we can witness the appearance of a new production of enamel on gilded copper. It is here, it seems, that champlevé on copper was born (a famous early example being the Ark of Abbot Boniface de Saint Foy, about 1120), obtained no more on hot bronze like the Celtic champlevé enamel, but on engravings obtained by chisel or acid corrosion. A transitionary technique (the same used for the Holy Crown of Hungary), had the main figure cut in the metal and the cloisonné wires added for the details of the drawing. At the death of abbot Begon III, one of the main patrons of goldsmithing and enamelling in Conques, this production declines and moves to new enamel centres source: Enamels of Limoges 1100-1350, AA.VV., Metropolitan Museum, 1996, New York).

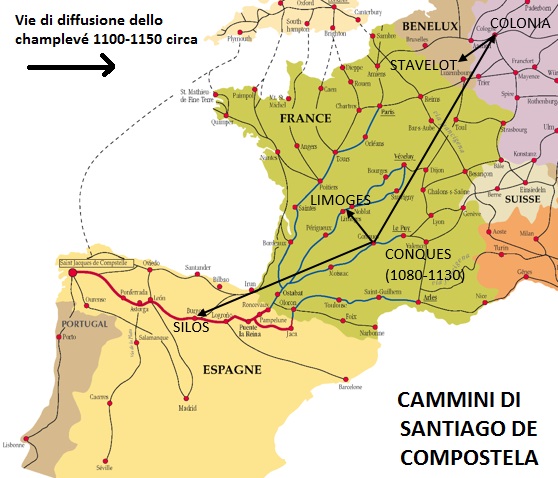

From the 12th century AD, we can see the foundation of new schools inheriting the champlevé style of Conques: the Limousine School (Limoges, France), the Mosan School (Lieges, Stavelot and Namur, Belgium), the Rhenish School (Cologne, Germany) and the Burgos School (Santo Domingo de Silos Abbey, Spain). It is most certainly not a case that the cities of Conques, Limoges, Cologne and Silos lay along the Route of Santiago de Compostela, as pope Callistus II and his successors favoured the pilgrimages to this sanctuary about this time (source: G. Hernández, Trabajo fin de grado - Esmaltes sobre Metal, Barcelona, 2014; pg.14-16). Throughout the Middle Ages, these workshops will produce a large quantity of religious artefacts such as reliquaries, caskets, altarpieces, tabernacles, patens, chalices and religious-themed plates.

Position of Conques, Limoges, Cologne and Silos on the Way to Santiago de Compostela.

Limoges was one of the first heirs of Conques thanks to their proximity, with an abundant and continuing production of cloisonné and champlevé enamels that went on perfecting over the next few decades. The first known example of Limoges champlevé enamel is the reliquary called the Casket of Bellac (1130). A few years later, the knowledge of the new technique reaches Cologne and hence spreads through the Rhenish and Mosan regions. In particular, it was probably Roger of Helmarshausen, a famous goldsmith and niello master, who spread this knowledge from Cologne to the Helmarshausen abbey, in Southern Germany. Sometime later, a monk known with the pseudonym Theophilus Presbyter compiled his knowledge of enamelling, niello and metalwork in the famous treatise “De diversis artibus”, also known as “Schaedula diversarum artium”. A few experts, such as Albert Ilg, Dodwell, Cyril Stanley Smith and Eckhard Freise, claim that Theophilus could be identified with Roger of Helmarshausen, as the two individuals leaved in Germany around the same period and because one of the manuscripts, we can see the inscription “Theophilus est Rugerus”. Despite this, other authors have expressed a few doubts on this identification, such as Maria Luisa Martin Anson. Nevertheless, we may suppose a dependance of Theophilus on Roger of Herlmarshausen, as they describe the same techniques.

Pastoral staff, champlevé on gilded copper, Host container and reliquary, 1150-1200, Castello Sforzesco, Milan

The Mosan school, in particular, has its most important centres in the Abbeys of Stavelot and St-Denis, where brillant goldsmiths and enamellists work, such as the famous Godefroy of Claire (active 1150-1173). Another representative of this school is Nicholas of Verdun, famous for his Reliquary of the Three Wise Men in Cologne (1190-1220) and the Klosterneuburg Altarpiece (Austria, 1171-1181).

Nicholas of Verdun worked on his masterpiece for 10 years and gave it to the prevost of Klosterneuburg in 1181. It was originally meant as a decoration of the pulpit of the abbey church. During the great fire on September 13th 1330, the monks saved the enamels by pouring wine on the flames, as the water supply was insufficient. Viennese goldsmiths re-arranged the enamel panels with the addition of six new panels and framed it so that the Altarpiece could be closed, and protected.

Shrine of the Three Kings (1190-1220) - Nicholas de Verdun, Cologne Cathedral.

The technique of champlevé on gilded copper rapidly arrives in Spain at least in the half of the 12th century. In the Kingdom of León, as we have already mentioned in the previous chapter, the influence of goldsmithing and Byzantine/Arabic enamels was already noteworthy in the area of Burgos, a city built about 850 on the border with the Caliphate of Cordova and one of the main stations in the Way of St. James. A noteworthy impulse to enamel art came from queen Sancha I of León (1032-1067), who called a few Byzantine goldsmiths and enamellists to Castile. In this fertile context, a new local school flourishes in the Abbey of Saint Dominic of Silos; thanks to its favourable position and the contacts with Limoges, the champlevé technique comes to Silos and acquires its own characteristics, in particular in the different enamel colours (such as a shiny green). Two noteworthy works of the period are the Urn of Saint Dominic (1165-1170) and the pastoral staff of abbot Juan II (1198). Simultaneously, in the Kingdom of Navarra, we can find the “Frontal de Aralar”, an antependium in the Sanctuary of St. Michael of Aralar, probably the work of a limousine goldsmith, with 39 enamel plates.

Among the four schools, only the one in Limoges managed to survive beyond the 12th century and, after some major periods of decay, managed to arrive to our days; this way, the Limousine enamellists had the possibility to experiment on complex and innovative techniques. In 1215, during the 4th Lateran Council, Pope Innocent III ordered the production of vessels for the reservation of the Eucharist, while in 1229 the Synod of Winchester decided that the so-called Eucharistic doves from the Limoges workshops (Opus Lemovicense) were fitting for this purpose. These decisions certainly had an important impact on the growth of Limoges during the 13th century, but at the same time, reducing its creative impulse in favor of a more standardized “mass” production.

According to recent independent studies by the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the University of Turin, during the period between the 12th and 13th century, we can see a change in the chemical composition of Limousine enamels. From the analysis at the spectrometer, we get the result that the enamels used until the end of the 12th century are chemically identical to the mosaic glasses of the Romans, while later there was a transition towards a new type of glass with raw materials from the Middle East. According to some experts, this can be explained with an initial recycling of Roman glass by the enamellists until the 1200, when the material was now disappearing. This discovery confirms also the accuracy and trustworthiness of Theophilus Presbyter, as he referenced this practice in De diversis artibus, Book 2, chapter 12.

LATE MIDDLE AGES

At the half of the 14th century, Limoges began a period of inexorable decline and it was in Siena (Italy) that a new technique appeared. The so-called champlevé basse-taille or translucent enamel on bas-reliefs consists of the chiseling of complex bas-relief figures and the application of translucent colored enamels, so that the different depths produce different color shades and the silver or gold base shines through the enamel.

A restorer at the Vatican Museums writes,

“The creation of translucent enamels is due to the fusion of two different technological experiences: the first one is the French tradition of working the metal base in relief; the second one is the Byzantine use of semi-transparent enamels”

Flavia Callori di Vignale, “Il Calice di Guccio di Mannaia nel Tesoro della Basilica di San Francesco ad Assisi”, page 133.

The first work of champlevé basse-taille is the Chalice of Nicholas IV, today in Assisi, created by Guccio di Mannaia, made of gilded silver, 22 cm high and decorated with 96 translucent enamels of little dimensions. The technique of Guccio di Mannaia gained immediately a great success and many silversmiths from Siena adopted and improved it for the creation of chalices and patens. We remind in particular Duccio di Donato, Tonino di Guerrino and Andrea Riguardi. In 1337, another artist from Siena, Ugolino di Vieri, created another masterpiece, the great Reliquary of the Corporal of Bolsena, in the Orvieto Cathedral, 139 cm tall, composed by 32 enamel scenes.

On the left: Reliquary of the Miracle of Bolsena, Cathedral of Orvieto, Ugolino di Vieri (1337-1339).

On the right: Chalice of Nicholas (1288-1292) by Guccio di Mannaia (Church of St. Francis, Assisi). This is the first example of basse-taille enamel.

The translucent enamel technique arrived in Spain under the influence of Catalan king James I of Aragon (d. 1276). In particular, Maiorca grew to prominence with a manufacture settled by goldsmiths from Provence, Siena and Naples, but also Valencia, generally associated with the name of Pere Berneç, a goldsmith active in the days of Peter the Ceremonious (d. 1387) and author of many sacred objects, including the golden altarpiece of the Girona Cathedral.

Altarpiece of the Girona Cathedral, art by Pere Berneç

About this time, Iran becomes the home of a new important production of enamel under the reign of Ghazan Khan (1271-1304). The enamels are in the style of miniature painting on white enamel with geometric and flower motifs, in the traditional Islamic style. The technique is commonly known as minakari, which means “paradise” from the prevalence of blue colors.

THE EXPERIMENTS AT THE TURN OF THE 15th CENTURY

The first documented proof of the existence of plique à jour enamel is an inventory of Pope Boniface VIII dated 1295, where it is referenced in Latin as smalta clara. Anyway, the first example that reached us is the Mérode Cup with cover, made of vermeil (gilded silver) in Bourgogne around 1400. The object takes the name of the ancient Belgian family Mérode, the original owners.

The Cup of Mérode, vermeil with plique-à-jour enamel, produced in Bourgogne about 1400.

In the years 1380-1420, the artists began to experiment on new forms of enamel decoration, more “courageous” than the previous techniques. In particular, this is the moment of the ronde bosse enamel, developed primarily in Paris and London. A possible reason for these new developments is that, following the Hundred Years’ War (1337-1453) and, in particular, the Massacre of Limoges (19 September 1370), the School of Limoges had gone in decay and some of the enamellists found refuge in Paris under the patron John of Valois, Duke of Berry. The ronde bosse enamels of the time are the Reliquary of Montalto (1377-1380), created in Paris by the goldsmith and valet Jan du Vivier and modified by a Venetian goldsmith’s atelier 60 years late; the Reliquary of the Holy Thorn (1380-1387), and the Golden Pony of Charles VI, and the Table of the Trinity, 44.5 cm tall. Noteworthy is also the famous Dunstable Jewel.

Three of the earliest "ronde bosse" enamels. On the left: Reliquary of the Holy Thorn, 1380, British Museum (London, United Kingdom); at the center, Golden Horse, 1404, Church of St. Anne (Altötting, Germany); on the right, Table of the Trinity, 1411, Louvre Museum (Paris, France)

The most ancient documents proving the existence of enamel in Czechia or Moravia date back to the kingdom of the House of Luxembourg. We may say that the use of enamel in the Gothic period was generally restricted to a few objects and exclusively meant to be a decorative complement to gemstones, who remained the primary ornamental element.

During the reign of Charles IV of Luxembourg, the first King of Bohemia who also held the crown of the Holy Roman Empire from 1355 to 1378, we can witness a cultural boom that led to a rapid growth in the arts, especially architecture and jewellery, as part of the expansion works on the capital city, Prague. For example, we can find decorative enamels even on the objects from the workshop of German-born jeweller Petr Parléř in Prague.

A noteworthy piece of the time is the reliquary of the Kolovrat family, produced about 1460-1470 by Martin of Hradčan, in a style that betrays the Hungarian origins of the artist.

An important artefact of the late-Gothic period with little green and blue enamel decorations is the cincture traditionally associated with Queen Elizabeth, the fourth wife of Charles IV, which is really a work from the second half of the 15th century.

In the early 15th century, Persian enamel came from Iran and Pakistan to China, where it was known as “Islamic ware” in the book Ge Gu Yao Lun.

THE RENAISSANCE: ENAMEL PAINTING & PAINTED ENAMEL

During the 15th century, Northern Italy, Venice in particular, switched from champlevé to painting on enamel, an imitation of painted porcelain.

Examples of painting on enamel from Northern Italy (Milan and Venice), 15th century

The greatest renovation in the field of enameling was the creation of painted enamel, almost contemporary in Italy and France. Jean Fouquet learned the art of enameling from Italian master Filarete and was the first to ever produce an enamel cameo with a technique similar to painted enamel and grisaille, a few years ahead. Enamel was now ready to become pure art: the plain and stylized figure typical of cloisonné and champlevé were abandoned in favor of the depths of design, as for the oil on canvas. The brightness improved even more with the transparences of the thin paillons of silver and gold. By the end of the 15th century, we have some 40 works attributed to the same author or atelier, known to the experts by the name “Pseudo-Monvaerni” after an inscription found on some of these works. The style has already the distinctive traits of émail peint, but nothing comparable to the more evolved paintings of the 16th century.

Self-portrait of Jean Fouquet, c. 1446

Flagellation, Pseudo-Monvaerni, painted enamel, 14x16 cm, (late 15th century)

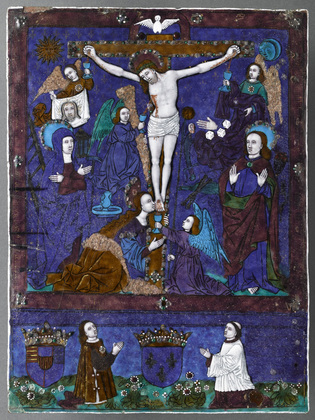

The earliest pure painted enamel work is a Crucifixion, by Nardon Pénicaud (1470-1542), dated 1503. Nardon was the head of a dynasty of enamellists from Limoges. The work, commissioned by René II, Duke of Lorraine (1451-1508), is now in the Museum of Cluny. In this period, the technique Grisaille is also born around 1530. The best creations of the period are hybrids with translucent enamels, grisaille, painted enamel and paillons. This technique will lead to the rebirth of Limoges. Amongst the best artists, we mention Pierre Courteys, Pierre Raymond, Nouailher, Jacques Laudin, Jean de Court and his daughter Susanne de Court, the first woman enamellist recorded by name. There are also a few anonymous artists such as the so-called Master of the Aeneid.

Crucifixion by Nardon Pénicaud, painted enamel, Limoges, 1503.

The most famous enamellist is certainly Léonard Limosin (1505-1577), the first to be officially recognized as valet and court painter. Limosin had been admitted to the School of Fontainebleau and he was able to produce hundreds of paintings with portraits or based on his own sketches. That is why he is considered one of the best exponents of Limoges enamel in the Renaissance.

Two works by Léonard Limosin.

On the left: Flagellation, enamel on copper, 18x25 cm, 1550. On the right: Portrait of the Count of Palatinate, Jean Philippe, 1550.

Grisaille Technique. On the left: Folly, by Jean Laudin (1616-1688). On the right: Florentine school mythological work.

About 1500, Man Singh I, rajah of Amber, welcomes the enamellists from Punjab (Pakistan) to Jaipur (present-day Rajasthan, India), turning the city and the nearby Lahore and Delhi into the main center of minakari enamel in India.

Back to the West, the sudden and rapid flourishing of artistic artisanship in Czechia during the 16th and 17th centuries is due to the reign of Rudolph II (1572-1612), who was a collector and created his own “Cabinet of curiosities” to gather the masterpieces of art and crafts that he received as a gift during his official visits. The Cabinet hosted works acquired across Europe. During the reign of Rudolph, Prague welcomed the greatest artists and craftsmen, including many renowned and skilled goldsmiths, who produced jewels not only for the aristocrats, but also for the wealthy citizens. The frequent presence of enamelled jewels in the portraits of the time show how the enamels were probably mistreated, considering the unfortunately low number of objects that have survived to this day. These objects of the period combined several different techniques born in the West, such as ronde bosse, basse taille and champlevé, with an alternation of transparent and opaque colours.

Towards the end of the 16th century, enamel art went into decline once again, both for a change of tastes and for the low quality of mass productions. The technique in use at the time, known as enamel painting, was almost an imitation of porcelain. We can see a triumph of miniatures on snuffboxes or table clocks and jewelry. The pictorial technique was perfect to interpret the new rococo taste for luxury items.

FROM THE 17th CENTURY TO OUR DAYS.

A new technique called “enamel miniature” appeared in Switzerland and France at the beginning of the 17th century. Jean and Henri Toutin from Genève invented the technique in 1632, when they began to apply a transparent enamel on little copper medals and decorated them with color oxides by brush on transparent enamel. One of their disciples, Jean I Petitot, is known as the Raphael of enamel for his perfect works, especially those produced from the sketches of Anton van Dyck using a color palette invented by chemist Turquet de Mayerme. The greatest portraitist was presumably Jean-Etienne Liotard (1702-1789).

Portrait of Louis XIV the Sun King, enamel miniature by Jean Petitot during the period 1649-1691.

In 1753, the first industrial manufacture of enamel opened in Battersea (England).

During a diplomatic travel across Western Europe in 1697-1698, Emperor Peter the Great of Russia met Charles Boit, a French-Swedish enamel miniaturist working at the court of William III of England. Fascinated by the technique, Peter began to invite Western enamellists at his court in the newly founded Saint Petersburg. The first Russian enamel miniaturist was Grigory Semyonovich Musikiysky from Moscow (1670-1740), who painted the first enamel portraits of the royal family. Another important name is that of Andrey Ovsov, who adopted a stippling (pointillé) style akin to the French and English miniaturists.

Finally, in 1763 the Orthodox archbishop of Rostov Arseniy Tarkovskiy opened the first atelier to produce enamel miniature icons: it is the famous finift technique that rapidly passed from a purely religious purpose to a wider profane use.

From 1845 to 1872, the famous porcelain manufacturer in Sèvres opened an atelier of enamel art. René Lalique was the last great enamellist at the time of the Art Nouveau.

Meanwhile, a Japanese former samurai, Kaiji Tsukenichi, discovered how to reproduce the Chinese cloisonné enamels and opened his famous manufacture in Nagoya, so important that it was recognized by the State. Enamel had already come to Japan a first time in 1620, but never enjoyed the same success that will continue till the 1960s with a flourishing of different techniques. Enamel is known in Japan as Shippō.

A pair of vases by Kaji Tsunekichi, Yūsen-Shippō (Japanese cloisonné), late 19th century

The end of the 19th century saw the art of portraits being abandoned because of the invention of the daguerreotype. A noteworthy exception was Carl Fabergé in St. Petersburg, who invented a new use of enamel, the guilloché technique, a sort of basse-taille on a metal base worked mechanically with a specific machine. He is famous for the Fabergé Eggs, jewels of great value under the Russian tsars.

An Italian representative of Art Nouveau, Vincenzo Miranda, goldsmith and silversmith from Naples, had one of his jewels exposed at the Universal Exposition of 1900.

In Austria, on the contrary, we can find the enamel paintings of Viennese silversmiths Hermann Ratzersdorfer and Hermann Böhm.

Czechoslovakia

In the 20th century, Czechoslovakia becomes an important centre of enamel art, especially since the 1960s (names of the authors sorted by birthdate) (source: Uměni emailu – Technika smaltu, Museo della Tecnica di Brno, 2017).

- Věra Janoušková (1922-2010). Although not an enameller herself, this artist produced many sculptures composed of recycled enamelled houseware, cut by flame and soldered to each other.

- Jan Nušl (1900-1986), a student at the Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design (VŠUP) in Prague. He gave a new life to the technique, teaching at the same Academy and educating two generations of enamel artists.

- Jana Cepková (born in 1939), a pupil of Jan Nušl and wife of Slovak artist Anton Cepká, one of the founders of the Czechoslovak Concretist Club. She won a prize at the International Biennial of Limoges in 1978 and she took part in several exhibitions abroad in Vienna, Hanau and Pfarnheim.

- Eva Žaková-Št’astna (1944), another student of Jan Nušl, who managed to renew traditional enamel with new technologies and techniques. In 1985, she organized even the Czekoslovak Contemporary Enameller’s Exhibition in the Prague Atrium, and also took part in it as an exhibitor.

- Eva Kučerová-Landsbergrová (1947-), she is an artist from Místek, in the Beskid Mountains. She was educated at the Secondary School of Applied Arts in the Moravian city of Uherské Hradiště, with a specialization in graphic design in 1967. Her works have been influenced by the woods and mountains of her homeland.

- Radka Urbanová (1947-), she studied at the School of Applied Arts in Prague. She began to practice enamelling in 1995. Her enamelled jewels and objects often combine stylized and humoristic creatures with the presence of mobile parts, like jewels. In 1998, she won the first prize at the International Jeweller’s Fair in Kecskemét and the 10th prize for Cloisonné Jewellery in Tokyo, under the category „New Proposals“. Today, she is the director of the Mňau Gallery.

- Alena Novaková (1929-1997), belonging to the second generation of Jan Nušl’s disciples at the Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design in Prague.

- Olga Francová, Alexandra Horová and Madla Cubrová (1962-), students at VŠUP, who formed together a short-lived women-only enamel art group. The artists continued their careers on separate ways.

- Veronika Richterová (1964-), after studying at the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague (VŠUP), she perfected the enamelling technique in Paris at the School of Decorative Arts, though never disdaigning the use of other materials and techniques. Her unique use of enamel is destined to the creation animal sculptures on non-conventional supports (such as snakes made of chimney tubes) and are covered in very shiny industrial enamels, often with a sense of humour or excess.

- Magdalena Urbanová (1971), the daughter of Radka Urbanová. She initially taught ethnology at the Charles University in Prague and later followed in her mother’s footsteps, studying goldsmithing. She has been working with enamel for about 20 years. She is also the author of the first book on hot enamel on metals in Czech language. She is the director of the permanent exhibition of enamel history in the Museum of Technique in Brno. She works with experimental technologies to get special effects from her enamels.

- Eliška Fuksová (1995-), she is the most representative of the current new generation of artists in the Czech Republic.

Italy

Amongst the greatest names of enamel artists of the 20th century, we can remember Robert Barriot in France, Egino Weinert in Germany, Giuseppe Guidi (1880-1931), Giuseppe Maretto (1908-1984) and Mario Maré (1921-1993) in Italy. These masters adopted a style that Maretto called "taglio molle" (soft cut) champlevé, where the contours were engraved in the raw enamel before firing, so that the enamels are separate from each other and the figures emerge in bas-relief.

Also in Italy, many designers such as Gio Ponti, Armando Pomodoro or Sottsass combined their forces with great enamellists such as Paolo De Poli, Franco Bucci, Franco Bastianelli or the Studio del Campo atelier, producing innovative effects for everyday design objects.

The foundation of C.K.I. in 1979 was one of the most important events that helped in the rebirth of enamel at an international level, through the cooperation of artists from around the world.

CONCLUSION

Over a period of 35 centuries, many enameling techniques have developed, passing through many populations distinguished by culture, religion and social background. They have been absorbed into and spread by many schools and artistic movements; yet the special fascination for this applied art has overcome every kind of obstacle, reaching our era almost untouched. It remains a difficult art for an élite of artists who have a passion for amazing results which become visible only after tens of firings in a kiln at 800°C. An unknown design of destiny has preserved these techniques and reached us almost unchanged.

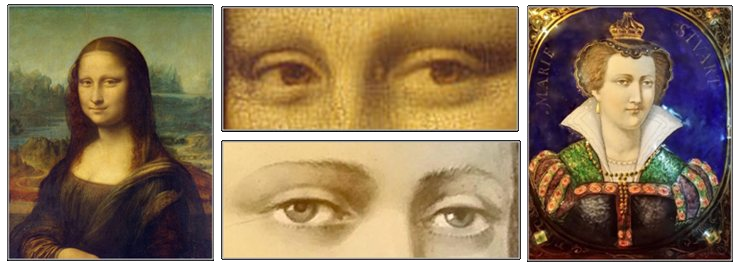

Let’s imagine Leonardo using enamels to paint one of his masterpieces, the Mona Lisa at the Louvre, today protected due deterioration from time: it would be as if it were still “new”, keeping its original bright colours just extracted from a kiln with the Maestro’s expert hands.

Comparison between the Mona Lisa or "Gioconda" by Leonardo da Vinci, 1503-1517 (on the left) and the enamel portrait of Mary Stuart,1558-1560 (on the right) probably by Leonard Limosin. While the enamelled skin of Mary Stuart is unchanged, the Gioconda's wrinkles are quite visible.