5. From Conques to the Medieval Schools

During the last decades of the 11th century, in the city of CONQUES in France, we can witness the appearance of a new production of enamel on gilded copper. It is here, it seems, that champlevé on copper was born (a famous early example being the Ark of Abbot Boniface de Saint Foy, about 1120), obtained no more on hot bronze like the Celtic champlevé enamel, but on engravings obtained by chisel or acid corrosion. A transitionary technique (the same used for the Holy Crown of Hungary), had the main figure cut in the metal and the cloisonné wires added for the details of the drawing. At the death of abbot Begon III, one of the main patrons of goldsmithing and enamelling in Conques, this production declines and moves to new enamel centres source: Enamels of Limoges 1100-1350, AA.VV., Metropolitan Museum, 1996, New York).

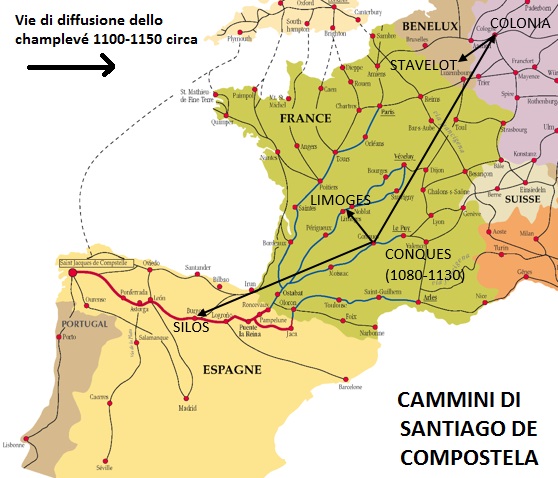

From the 12th century AD, we can see the foundation of new schools inheriting the champlevé style of Conques: the Limousine School (Limoges, France), the Mosan School (Lieges, Stavelot and Namur, Belgium), the Rhenish School (Cologne, Germany) and the Burgos School (Santo Domingo de Silos Abbey, Spain). It is most certainly not a case that the cities of Conques, Limoges, Cologne and Silos lay along the Route of Santiago de Compostela, as pope Callistus II and his successors favoured the pilgrimages to this sanctuary about this time (source: G. Hernández, Trabajo fin de grado - Esmaltes sobre Metal, Barcelona, 2014; pg.14-16). Throughout the Middle Ages, these workshops will produce a large quantity of religious artefacts such as reliquaries, caskets, altarpieces, tabernacles, patens, chalices and religious-themed plates.

Position of Conques, Limoges, Cologne and Silos on the Way to Santiago de Compostela.

Limoges was one of the first heirs of Conques thanks to their proximity, with an abundant and continuing production of cloisonné and champlevé enamels that went on perfecting over the next few decades. The first known example of Limoges champlevé enamel is the reliquary called the Casket of Bellac (1130). A few years later, the knowledge of the new technique reaches Cologne and hence spreads through the Rhenish and Mosan regions. In particular, it was probably Roger of Helmarshausen, a famous goldsmith and niello master, who spread this knowledge from Cologne to the Helmarshausen abbey, in Southern Germany. Sometime later, a monk known with the pseudonym Theophilus Presbyter compiled his knowledge of enamelling, niello and metalwork in the famous treatise “De diversis artibus”, also known as “Schaedula diversarum artium”. A few experts, such as Albert Ilg, Dodwell, Cyril Stanley Smith and Eckhard Freise, claim that Theophilus could be identified with Roger of Helmarshausen, as the two individuals leaved in Germany around the same period and because one of the manuscripts, we can see the inscription “Theophilus est Rugerus”. Despite this, other authors have expressed a few doubts on this identification, such as Maria Luisa Martin Anson. Nevertheless, we may suppose a dependance of Theophilus on Roger of Herlmarshausen, as they describe the same techniques.

Pastoral staff, champlevé on gilded copper, Host container and reliquary, 1150-1200, Castello Sforzesco, Milan

The Mosan school, in particular, has its most important centres in the Abbeys of Stavelot and St-Denis, where brillant goldsmiths and enamellists work, such as the famous Godefroy of Claire (active 1150-1173). Another representative of this school is Nicholas of Verdun, famous for his Reliquary of the Three Wise Men in Cologne (1190-1220) and the Klosterneuburg Altarpiece (Austria, 1171-1181).

Nicholas of Verdun worked on his masterpiece for 10 years and gave it to the prevost of Klosterneuburg in 1181. It was originally meant as a decoration of the pulpit of the abbey church. During the great fire on September 13th 1330, the monks saved the enamels by pouring wine on the flames, as the water supply was insufficient. Viennese goldsmiths re-arranged the enamel panels with the addition of six new panels and framed it so that the Altarpiece could be closed, and protected.

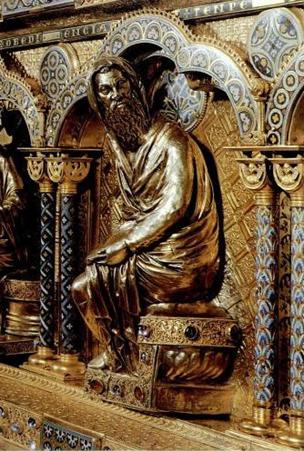

Shrine of the Three Kings (1190-1220) - Nicholas de Verdun, Cologne Cathedral.

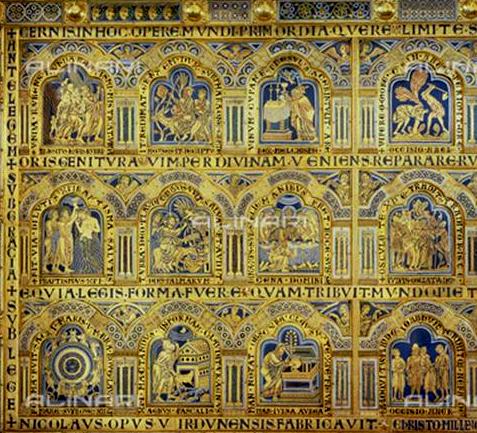

Klosterneuburg altarpiece, Nicholas de Verdun. Detail of some enamelled plates.

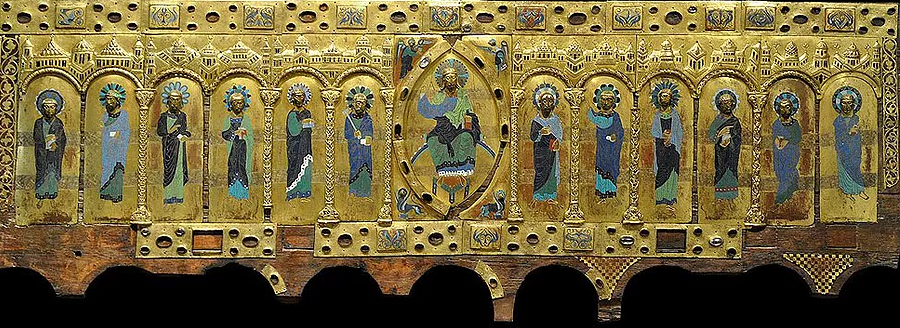

The technique of champlevé on gilded copper rapidly arrives in Spain at least in the half of the 12th century. In the Kingdom of León, as we have already mentioned in the previous chapter, the influence of goldsmithing and Byzantine/Arabic enamels was already noteworthy in the area of Burgos, a city built about 850 on the border with the Caliphate of Cordova and one of the main stations in the Way of St. James. A noteworthy impulse to enamel art came from queen Sancha I of León (1032-1067), who called a few Byzantine goldsmiths and enamellists to Castile. In this fertile context, a new local school flourishes in the Abbey of Saint Dominic of Silos; thanks to its favourable position and the contacts with Limoges, the champlevé technique comes to Silos and acquires its own characteristics, in particular in the different enamel colours (such as a shiny green). Two noteworthy works of the period are the Urn of Saint Dominic (1165-1170) and the pastoral staff of abbot Juan II (1198). Simultaneously, in the Kingdom of Navarra, we can find the “Frontal de Aralar”, an antependium in the Sanctuary of St. Michael of Aralar, probably the work of a limousine goldsmith, with 39 enamel plates.

St. Dominic Urn, Silos, Spain, 12th century

Aralar frontal - altarpiece from the Sanctuary of St. Miguel de Aralar, Navarra, 12th century.

Among the four schools, only the one in Limoges managed to survive beyond the 12th century and, after some major periods of decay, managed to arrive to our days; this way, the Limousine enamellists had the possibility to experiment on complex and innovative techniques. In 1215, during the 4th Lateran Council, Pope Innocent III ordered the production of vessels for the reservation of the Eucharist, while in 1229 the Synod of Winchester decided that the so-called Eucharistic doves from the Limoges workshops (Opus Lemovicense) were fitting for this purpose. These decisions certainly had an important impact on the growth of Limoges during the 13th century, but at the same time, reducing its creative impulse in favor of a more standardized “mass” production.

According to recent independent studies by the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the University of Turin, during the period between the 12th and 13th century, we can see a change in the chemical composition of Limousine enamels. From the analysis at the spectrometer, we get the result that the enamels used until the end of the 12th century are chemically identical to the mosaic glasses of the Romans, while later there was a transition towards a new type of glass with raw materials from the Middle East. According to some experts, this can be explained with an initial recycling of Roman glass by the enamellists until the 1200, when the material was now disappearing. This discovery confirms also the accuracy and trustworthiness of Theophilus Presbyter, as he referenced this practice in De diversis artibus, Book 2, chapter 12.

Eucharistic dove, used as a tabernacle, produced in Limoges c. 1215-1235. Metropolitan Museum, New York. Gilded copper with champlevé enamels.

At the half of the 14th century, Limoges began a period of inexorable decline and it was in Siena (Italy) that a new technique appeared. The so-called champlevé basse-taille or translucent enamel on bas-reliefs consists of the chiseling of complex bas-relief figures and the application of translucent colored enamels, so that the different depths produce different color shades and the silver or gold base shines through the enamel.

A restorer at the Vatican Museums writes,

“The creation of translucent enamels is due to the fusion of two different technological experiences: the first one is the French tradition of working the metal base in relief; the second one is the Byzantine use of semi-transparent enamels”

Flavia Callori di Vignale, “Il Calice di Guccio di Mannaia nel Tesoro della Basilica di San Francesco ad Assisi”, page 133.

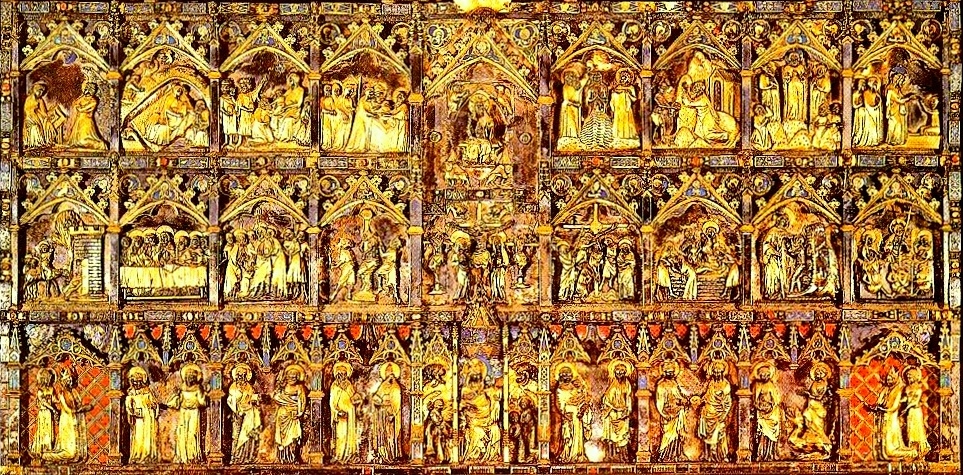

The first work of champlevé basse-taille is the Chalice of Nicholas IV, today in Assisi, created by Guccio di Mannaia, made of gilded silver, 22 cm high and decorated with 96 translucent enamels of little dimensions. The technique of Guccio di Mannaia gained immediately a great success and many silversmiths from Siena adopted and improved it for the creation of chalices and patens. We remind in particular Duccio di Donato, Tonino di Guerrino and Andrea Riguardi. In 1337, another artist from Siena, Ugolino di Vieri, created another masterpiece, the great Reliquary of the Corporal of Bolsena, in the Orvieto Cathedral, 139 cm tall, composed by 32 enamel scenes.

On the left: Reliquary of the Miracle of Bolsena, Cathedral of Orvieto, Ugolino di Vieri (1337-1339).

On the right: Chalice of Nicholas (1288-1292) by Guccio di Mannaia (Church of St. Francis, Assisi). This is the first example of basse-taille enamel.

The translucent enamel technique arrived in Spain under the influence of Catalan king James I of Aragon (d. 1276). In particular, Maiorca grew to prominence with a manufacture settled by goldsmiths from Provence, Siena and Naples, but also Valencia, generally associated with the name of Pere Berneç, a goldsmith active in the days of Peter the Ceremonious (d. 1387) and author of many sacred objects, including the golden altarpiece of the Girona Cathedral.

Altarpiece of the Girona cathedral by Pere Berneç.

Cup of the Duchesse of Mallorca, half 14th century, 25 cm high x 15 cm diameter, Gothic style. Louvre Museum (Inventory number OA 3359).

A representative of the Valencia school is goldsmith Pere Berneç, author of several religious works with translucent enamel from 1350 to 1380. Influenced by the Siena style, the artist worked at the court of king Peter the Ceremonious (d. 1387), and produced enamelled silver altarpieces for the chapel of the Royal Palace of Barcelona (1360) and for the cathedrals of Valencia and Mallorca (the latter working with Pere Perpinyà), but none of them survived to us. We can still see the Girona Cathedral altar, made with Ramon Andreu (1358) and the three enamelled crosses in the same Church (1350-1360). From 1376, the works of the Aragona Crown are four-handed products created with disciple Bertomeu Coscolla (source: G. Hernández, Trabajo fin de grado - Esmaltes sobre Metal, Barcelona, 2014; pg.27ss).

Moving to the Orient, c. 1300 the technique of enamelling arrives to Persia for the very first time, following the conversion of Ghazan Khan, the seventh sovereign of the Mongolian Ilkhanate, to Islam (1295-1304). The technique in this territory adapted to the subjects of Islam, such as geometric patterns and flowers, with brilliant colours and a preference for blue. This characteristic owed it the name of minakari, used in India and Iran, coming from Persian word minoo, meaning “heaven”. In the following centuries, the technique will spread to China in the 14th century (source: Gioielli dall'India dai Moghul al Novecento, vedi estratto)